Peter Palese has spent a long time thinking about how to improve the flu vaccine.

"Many, many decades," he said from his lab at Mt. Sinai's Icahn School of Medicine, where he chairs the microbiology department.

He feels his team is now getting close.

"We're really at the edge right now where I think we will have something much better," he said. "We're talking about years, but we are not talking about decades."

Palese is one of several scientists working on what they call the holy grail of flu: a universal vaccine, one that would protect against all strains of the virus and be durable for multiple years – if not a lifetime.

In order to do that, Palese's team built a new virus, one that doesn't exist in nature. It's the basis of a vaccine that's now in two phase 1 clinical trials, funded by British drug- and vaccine-maker GlaxoSmithKline and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Initial results are expected within a year.

Calls for a universal flu vaccine crescendoed during this year's flu season, one of the most severe on recent record. But flu always takes a major toll, hospitalizing as many as 710,000 people and killing between 12,000 and 56,000 each season in the U.S. alone, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"We almost get flu fatigue," said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. "It's not something that just comes once in a generation, so you get used to it — you get used to the fact that there's a lot of morbidity and mortality, and when you get used to those chronic things, you don't get stirred up by them very much."

Fauci is stirred up.

The leader of the National Institutes of Health's second-largest unit since 1984, his office walls are covered with photos of him with previous presidents, magazine features and recognition for his work in public health. He recounts a meeting with Bill Clinton in 1996 to discuss AIDS research, which resulted in Clinton announcing the formation of a national vaccine research center five months later.

Now, Fauci's added flu to his top priorities, announcing a strategic plan at the end of February to develop a universal vaccine. Among the criteria: it should be at least 75 percent effective, meaning it prevents at least three-quarters of flu infections.

That in itself would be a vast improvement over the current seasonal flu vaccine, which has varied in effectiveness from less than 10 percent to, at its best, about 60 percent. This season's vaccine was about 36 percent effective.

The problem is the changing nature of the flu virus.

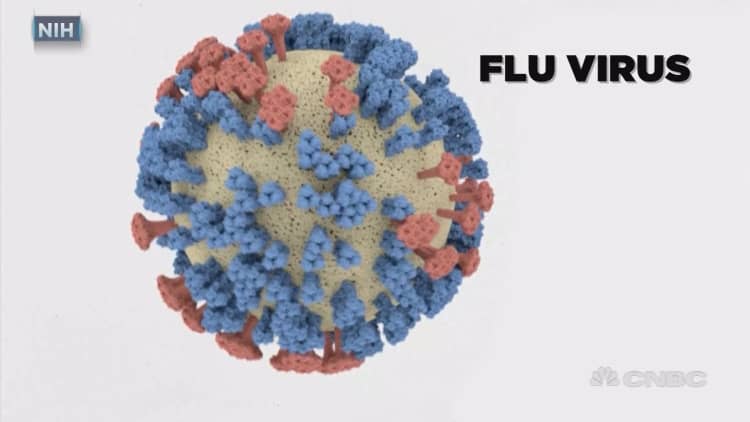

Influenza is characterized by two proteins on the virus's surface: hemagglutinin and neuraminidase (the H and the N in the names of A strains, like H3N2, and H1N1). Hemagglutinin enables the virus to enter human cells, and it's the target of current seasonal flu vaccines.

Those proteins are composed of a head and a stem, "kind of like broccoli with a stalk," Fauci explained. The head is the part that mutates each season — and it's also the part the current flu vaccine targets.

"The bad news is that when the body sees the molecule that's the head and the stalk, it preferentially likes to make a response against the head," Fauci said, describing a phenomenon known as immunodominance.

About a decade ago, researchers discovered that part of the virus — the stalk — doesn't change season to season.

"Once we recognized that," Fauci said, "the real problem and the stumbling block is: how do you get the body to preferentially make a response against that molecule?"

Enter Palese's new virus.

"We make vaccines which basically present these conserved areas only, and by making immune response against those... it should be as good as a measles vaccines or a rubella vaccine or a mumps vaccine," Palese explained.

With initial results expected within a year, Palese says it will still be many more years before a potential vaccine would be commercially available.

"We're talking about years," Palese said, "but we're not talking about decades."

GSK, which is funding one of the clinical trials, is among a number of large pharmaceutical companies working on universal flu vaccines — others include Johnson & Johnson and Sanofi Pasteur.

"It's not simple to do this," said GSK's Dr. Leonard Friedland, emphasizing that until a universal vaccine becomes available, the seasonal flu shot still provides significant benefit.

"We don't want to lose sight of what we have today," Friedland said. "But we do want to focus on the future."

More from Modern Medicine:

Blood test can detect Alzheimer's decades before symptoms

Cancer research breakthrough shows a better way to predict drugs that will work

Study suggests anti-overdose med naloxone increases reckless opioid use