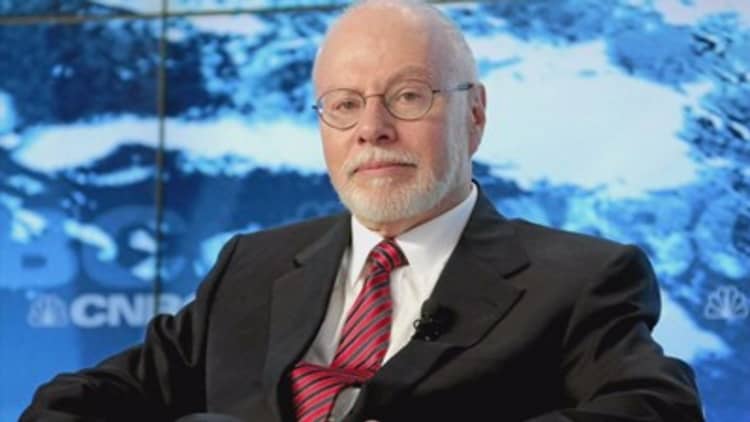

Billionaire hedge fund manager Paul Singer and fellow activist investor Charles John Wilder have their work cut out for them with their latest gamble: overhauling a major player in the utility space, a sector that has humbled some of the world's savviest investors in recent years.

The two are behind a plan to transform NRG Energy, the nation's largest independent power producer, from a sprawling giant with significant clean energy holdings to a smaller and simpler generator and seller of electricity.

If they succeed, they will at least create a more valuable company for shareholders. But they also stand to reshape the competitive landscape through major acquisitions and score a win in an industry that has confounded the likes of Goldman Sachs and Warren Buffett.

Analysts say the surge in NRG's share price last week reflects investors' confidence in Wilder, 59, who won a board seat in February after partnering with Singer, 72, to push for change. Now the head of energy investment firm Bluescape Energy Partners, Wilder made his name by turning around Texas power company TXU before selling it in the largest ever leveraged buyout in 2007.

Singer's Elliott Management owns a nearly 6 percent stake in NRG, while Bluescape owns about 2.8 percent, according to FactSet.

NRG Energy 10-year stock performance

At NRG, Wilder and CEO Mauricio Gutierrez aim to shrink the business after shareholders rebelled against an aggressive expansion into renewable power and sustainable energy spearheaded by former chief executive David Crane over the last decade.

The company will try to generate about $1 billion in cost savings, while seeking to sell off all or part of its renewable energy business, as well as a portion of its conventional energy portfolio. That will reduce NRG's debt load, largely tied to renewable projects, and generate up to $6.3 billion to invest in higher-yielding businesses or fund shareholder payouts, the company said.

NRG has not disclosed which power plants will remain in its portfolio once the transformation plan is complete, but analysts say even its best coal, natural gas and nuclear facilities, many located in Texas, face a challenging environment.

'Gas and government'

Power producers have struggled to figure out a winning model since the late 1990s, when many states broke up large utilities to allow competition in segments like generating power and selling electricity to end users.

To some degree, that's simply due to the challenge of operating businesses that invest in assets with high sunk costs within a market that's difficult to predict, said Tony Clark, a former commissioner of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. But there are other recent factors at play.

"The pressures that are facing it now are different," said Clark, now a senior adviser at law firm Wilkinson Barker Knauer. "In recent years, it's been a combination of gas and government."

The unexpected boom in U.S. natural gas production over the last decade has pushed down power prices, making it harder for companies that operate plants to turn a profit.

At the same time, state and federal subsidies and other support for renewable energy projects have boosted competition from wind and solar power. Since wind and solar power have very low marginal costs, transmission companies put electricity generated by renewables on their lines first, and turn to natural gas and coal plants to meet remaining power demand.

Much of NRG's business is focused on selling electricity generated at power plants into the wholesale market, where utilities buy it and then sell it to customers. With power prices low, it's hard for power generation businesses to make money in this line of work. But NRG also has a retail business that buys electricity on behalf of customers, and that segment does well when power prices fall.

The more profitable retail business will account for a bigger share of earnings after the transformation. Analysts have generally expressed support for that broad strategy.

"Pairing those two businesses can reduce the overall volatility of earnings and can offset either side in a market dislocation," said Travis Miller, director of utilities at investment research firm Morningstar.

But many remain concerned about what will be left of the generation business.

"They have a generation fleet in Texas that's mostly weighted towards baseload nuclear and coal," said Neel Mitra, director of utilities and power research at investment bank Tudor Pickering Holt. "Those assets are in a really tough environment largely because natural gas prices are low and wind is crushing the off-peak pricing."

While the plan improves the company's financial standing by reducing debt, it introduces risks to its business, according to ratings agency Moody's.

"The scale of the divestiture will significantly reduce NRG's size and cash flow diversity, an important consideration for companies exposed to volatile commodity prices," Moody's analyst Toby Shea wrote in a research note.

"Because NRG's renewable business is an important source of stable cash flow and long-term growth, its partial or full sale is credit negative for NRG," he said.

Tangled web of power producers

NRG itself was swept up in a wave of bankruptcies about 15 years ago, the result of power companies spending big to acquire new plants, only to be laid low by a slump in power prices and the Western energy crisis of 2000 and 2001.

The company entered a period of recovery as former CEO David Crane expanded into regions like Texas and diversified into retail electricity while other producers like Calpine and Dynegy filed for bankruptcy.

The 2007 buyers of Wilder's former company TXU, now known as Energy Future Holdings, saw their investment go sour as low natural gas prices crushed their expectations that their coal assets would become more competitive. Energy Future filed for bankruptcy in 2014 under the weight of more than $40 billion in debt — one of the largest bankruptcies in history.

The private equity firms that spearheaded the 2007 buyout — Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, TPG Capital and Goldman Sachs' buyout arm — wrote down billions. Berkshire Hathaway CEO Warren Buffett also lost nearly half of his $2 billion investment in the company's bonds.

Buffett and Singer are now feuding over Berkshire's proposed $9 billion buyout of Energy Future's transmission business, Oncor.

Yet another Energy Future-linked entity could play a part in NRG's transformation. Vistra Energy, a power producer that emerged from Energy Future's bankruptcy, has entered talks to merge with Dynegy, the Wall Street Journal reported in May.

Morgan Stanley and Tudor Pickering Holt both identified Dynegy as a potential acquisition target for NRG. Dynegy represents one of the only shots NRG has of picking up a large portfolio of combined cycle plants, the most efficient type of natural gas facilities, analysts say.

Buying Dynegy would allow NRG to re-enter the Pennsylvania-New Jersey-Maryland market with more competitive assets following the bankruptcy of its GenOn unit, which primarily operated coal plants in the region.

Ultimately, buying these combined cycle plants is the best option for generators, said Mitra, the Tudor Pickering Holt analyst. In his view, Vistra likely needs Dynegy's assets more than NRG, which would be in better financial shape if the transformation goes according to plan.

"They bought themselves a lot of time with the cost cuts," he said. "They are looking at buying assets, but they don't necessarily need to do it right away."