Gabriel Sarah's heart is a medical mystery.

Since 2012, the 37-year-old pediatric anesthesiologist has had ventricular tachycardia, causing the lower chamber of his heart to beat abnormally fast.

"It can cause syncopal episodes, which are times when I lose consciousness, I can't see, I can't hear, the room goes black and I can collapse," Sarah told CNBC.

His doctors don't know why.

"I've had a bunch of studies — genetic studies, imaging studies, including an MRI of my heart, an echocardiogram — and everything has been negative, which is good and bad," Sarah said.

He's one of millions of Americans with abnormal heart rhythm, or cardiac arrhythmia. The most common form, called atrial fibrillation, affects as many as 6 million people in the U.S., and at its most serious, it can lead to heart failure or stroke.

There are therapies that can treat abnormal heart rhythm, but first doctors need good ways to monitor it. For decades, cardiologists have used devices known as Holter monitors, which are about the size of a deck of cards. They're typically worn for two days, with multiple electrodes connected to the chest and torso.

Sarah tried that, as well as an event monitor, worn for a month.

"To wear something like that for 48 hours or a month is very cumbersome," he said. "It prevents you from really getting very active exercise, or doing anything requiring minimal exertion. It's difficult to wear under your clothing, it's difficult to work, and it's difficult to travel."

Times when, as Sarah points out, it's most important to track the heartbeat.

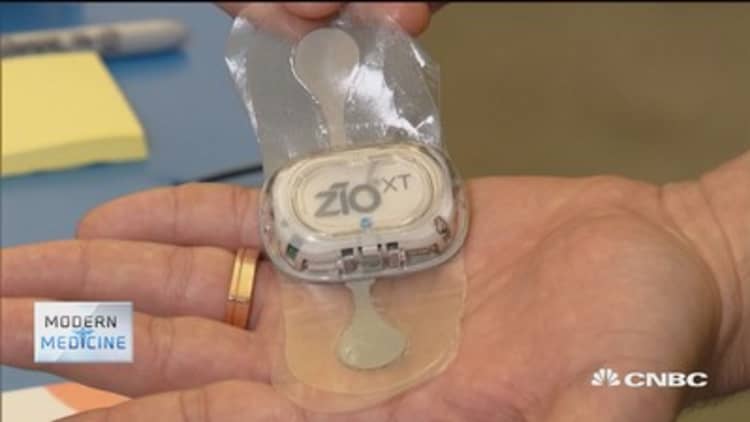

So Sarah's cardiologist fit him with a Zio patch, made by young San Francisco-based company iRhythm Technologies. A three-inch patch worn continuously for two weeks, the Zio is set to displace Holter monitors almost completely, said JPMorgan analyst Mike Weinstein.

"They're still using a technology that's been around for 30-plus years, and it looks like that's going to go away," Weinstein said.

The technology appears so simple that cardiologist Edward Gerstenfeld said he was baffled it hadn't come along earlier.

"When I first saw it, I thought, 'Well, why didn't I think of this?'" said Gerstenfeld, who treats Sarah at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center. "The unique thing is that the older monitors have been around for so long, that this was such a dramatic improvement in terms of patient comfort that it just made sense."

The patch — which encases a chip and two electrodes — also generates huge amounts of data: 30,000 pages of information on a patient's heartbeat, which iRhythm analyzes and distills into a 15-page report for physicians.

"They will have more information about abnormal heartbeats than any database in the world," Weinstein said. He has recommended buying iRhythm stock since November, after the company's October initial public offering, led by Weinstein's firm, JPMorgan. The stock is up 20 percent since the IPO, giving iRhythm a market capitalization of about $700 million.

The company's database grows with each new patient, and will get more useful with each new addition, said iRhythm CEO Kevin King.

"That massive amount of data that gets curated by these algorithms really is under the control of a machine-learned capability, and it gets smarter as we put more and more data into the database," King said. "That improves the time to diagnose, that lowers the cost of diagnosis, and really gets the business to go in a faster way."

The Zio patch is more expensive than older monitors: about $360 for Medicare versus $100 to $150 for Holter monitors, King said. The higher price can occasionally cause trouble with insurance reimbursement, though Gerstenfeld estimated about 80 percent of insurance companies cover the patch.

More data on its usefulness will help, Weinstein said. The company did a study comparing data generated by the Zio to that from Holter monitors in people with atrial fibrillation, and found that physicians changed their medical decisions 28 percent of the time because of the Zio report, according to King.

"A lot of that had to do with different levels of drugs or discontinuation of different heart-related drugs, different procedures, and, in some cases, life-critical things like pacemakers needing to be implanted," King said. "It was a very powerful study."

But the Zio isn't suitable for every situation, Gerstenfeld said.

"It's not transmitting currently in real time, so if someone has something really worrisome, like they're passing out, you want to know right away if that happens," Gernstenfeld said. "The Zio patch — it's recording for two weeks, then the patient sends it in, then we get the report a week later — so there's a couple week delay before we get the report."

The market opportunity, according to Weinstein, is huge: there are more than 4 million cardiac diagnostic tests done in the U.S. every year, putting the market size at more than $1.5 billion, he estimates. The company said in December it expected to have more than $62 million in 2016 revenue.

Sarah, despite the mysteriousness of his heartbeat, said his condition is well-managed. In addition to having used the Zio, he has an implanted cardiac monitor made by Medtronic designed to capture infrequent episodes like his. And he says he'd never go back to a Holter monitor.

"My opinion is that the Zio patch basically renders the Holter monitor useless," Sarah said. "It was an amazing experience. I forgot it was on during multiple occasions, and it was better than any other cardiac monitoring experience that I ever had."